Feature Stories | Feb 27 2008

By Greg Peel

Under normal economic cycles, strong economic growth leads to increased inflation, as incomes and wages increase and demand for commodities and consumer goods pushes prices up. When this occurs, central banks raise interest rates to curb economic growth, demand falls, and prices begin to fall back, thus dousing the inflation threat. It usually follows that inflation, which has the power to undermine the value of all assets, falls when economic growth falls.

Early this month the US Federal Reserve cut its US economic growth forecast for 2008 from an average of 2.15% to an average of 1.65%. But many an observer believes the US is actually in recession already, suggesting a negative growth rate. The Fed also increased its core inflation forecast for 2008 from an average of 1.95% to 2.25%. But many an observer scoffs at such low numbers, given food and energy prices are not included in this core measure due to their volatility.

Either way, the Fed lowered its economic growth forecast while raising its inflation forecast. The Reserve Bank of Australia has similarly revised its forecasts recently, suggesting that while Australian economic growth should fall back to trend levels inflation is expected to continue rising into 2010 if monetary policy action is not taken.

In each case, growth forecasts are falling while inflation forecasts are rising. The RBA is tightening monetary policy by raising rates, but the US is easing monetary policy to save the economy. On one side inflation is caused by rising prices. On the other it is caused by increased money supply, which is exactly what the Fed is doing by easing monetary policy. Hence the US dollar is falling while the Aussie dollar is rising. In the meantime, the European Central Bank has also made similar economic growth and inflation forecast changes. The ECB has been concerned about inflation through the duration of the credit crunch, and as such has left its rates unchanged, despite pumping billions of euros into the banking system.

What we are seeing is a stagflationary scenario. In the last week or so, oil, natural gas, platinum, wheat, corn and tin have hit all-time highs. Copper and aluminium have rebounded to almost two-year highs. Commodities indices are also reaching all-time or multi-year highs. At the same time consumer confidence in the old-world economies of the US, UK and Europe has crashed. Indications are that all will suffer economic slowdowns, with some observers expecting Europe and the UK to be particularly badly hit despite the fact the focus has to date been on the US.

Stagflation implies that incomes will fall and jobs will be lost at the same time as prices increase. This is a double-whammy effect that was last experienced throughout the 1970s. Global recessions followed. Central banks have since changed their attitudes to monetary policy, realising that inflation cannot be allowed to run away at the expense of economic growth management. The challenge for central banks today is ensure inflation does not run away as the world deals with trying to ease the downward pressure on the global economy in the face of the credit crunch. But there is faith being placed in the expectation slowing economies will naturally affect a fall in inflation eventually. While stagflation may appear to be upon us right now, it may yet prove a short-term phenomenon. At least that’s what central banks are hoping.

If they are wrong, then it’s time to get out your bell-bottoms, body shirts and six-inch-wide ties, platforms and perms. Are we really facing a return to the seventies?

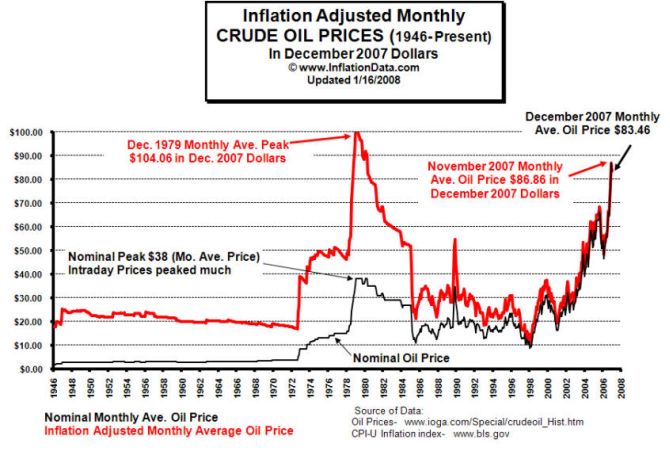

In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched attacks against Israel and thus began the Yom Kippur War. In retaliation for the West’s support of the state of Israel, the Arab members of OPEC decided to embargo oil shipments. In the blink of an eye, the price of oil doubled, rising from US$20/bbl to US$40/bbl if measured in December 2007 US dollars. Suddenly the developed world woke up to the fact it was totally dependent on Middle Eastern oil. OPEC continued to keep the world at bay during the seventies, and between ’73 and ’78 the (real) price continued to drift up to US$50/bbl. In 1978, the Iranian Revolution deposed the Shah and sent oil production in the country into disarray. The oil price peaked in 1979 at just over US$100/bbl in real terms.

And here we are again.

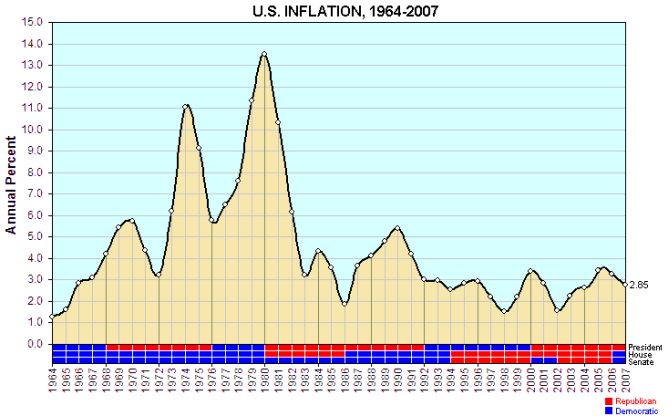

It was the “oil shocks” of the seventies that caused stagflation. The sudden jump in the price of oil was immediately crippling for Western economies. Production costs went through the roof and consumer prices followed. Trade unions, at their most powerful in the seventies, pushed for higher wages to compensate for increased prices. The wage/price spiral ran out of control. The rate of inflation in the US reached over 13% in 1980.

It was a case of a “supply shock”. The price of oil rose not because of increased demand, but because supply was suddenly curtailed. When the global economy receded, so too did the price of oil. And we all stopped driving V8 gas-guzzlers and embraced the toy cars being produced in Japan. OPEC could not hold out, and the oil price fell quickly back to US$20/bbl again.

But the oil shock was not the only reason inflation reached double digits in the seventies. Returning to those powerful trade unions, the seventies were a time of workplace reform which saw the collapse of the old production line system. Why this may have been to the benefit of downtrodden workers, it also meant a collapse in global productivity.

And prior to the oil shocks global central banks had not been concerned about inflation, they were only concerned with economic growth. Thus when inflation led to economic hard landing, central banks responded by putting interest rates down. Feeding money into the system only served to fuel inflation further. It was only when inflation rose into double digits that central banks realised they would have to abandon their attempts to stimulate growth and address the spiralling problem. They put rates back up, and inflation fell to 2% by 1986. Ever since 1980, global central banks have considered inflation as their biggest threat and thus attempted to control it.

The oil price is now again above US$100/bbl, but this time it has taken seven years to rise from US$20/bbl. This time it’s not a supply shock, but a significant growth in demand stemming from the industrialisation of China and other developing nations. This industrialisation has also driven the price of hard commodities such as base metals and bulk minerals to never before seen prices.

The same effect has been felt in global food prices, but in the case of food there it is another double-whammy. The growing wealth of the populations of developing nations has meant a greater demand for food more favoured by the west, and a greater demand for meat, which was previously only an occasional indulgence for subsistence peasants. This demand has pushed up the price of grains and livestock, both directly and indirectly given the animals also eat grains. At the same time, global ethanol production has skyrocketed in response to the price of crude. Whereas once a growth in global food demand could be met by giving over more land to farming, today the amount of land farmed for food production has rapidly decreased in favour of growing grains for ethanol production. What is thus occurring is an oil-food spiral.

So if that’s the case, why has inflation in the US remained in the low single digits since the early nineties? It is not because monetary policy has been restrictive all that time. Indeed, in 2004 the US interest rate was reduced to only 1%.

The answer lies in what is loosely described as globalisation, and in the technology revolution. The industrialisation of the economies of China et al has brought millions of new workers into the global economy at much lower wages than the West must pay. Hence there has been an enormous jump in global productivity as Western companies have outsourced their manufacturing processes to the much cheaper developing world. This has ensured price deflation of manufactured goods. The capacity to manage far-flung enterprises has been made possible by the internet, and the computer chip has served to reduce both the size and cost of goods. Remember the first mobile phones? The rapid transition from house-brick to Dick Tracy watch and the consequent reduction in cost is deflation at work. And one element that is easy to overlook is that of storage. With so much information being able to be stored on a chip, global storage costs have plummeted.

In simple terms, the inflationary force of rising global commodity demand has been met by the deflationary force of rising global supply of cheaper goods. The rapid growth of developing economies has both fuelled and quelled inflation.

But now it seems that all of a sudden inflation is a problem once more. 2008 alone has seen a substantial jump in commodity price indices. Central banks are quickly revising inflation forecasts and either raising rates or holding off on lowering them (with the exception of the Fed, which has its fingers crossed). What has happened?

Two things have happened. The immediate problem has taken us back to the seventies again in terms of the “supply shock”. Wild weather in China and Australia and power outages in China and South Africa in particular have pushed up the prices of hard and soft commodities across the globe. In the case of oil, the Middle East is once again back in the frame with tensions in Iraq and Iran causing supply concerns and further problems have been experienced in the significant oil producing nations of Nigeria and Venezuela.

This is one reason why prices have made an alarming jump just recently, causing central banks to reassess their inflation outlooks. However, as the current problems are considered as “shocks” consensus among economists is that while higher inflation is now expected for longer, once such problems are addressed inflationary pressure should ease. The US economy is slowing, and a trickle-down effect should be felt across the globe, leading to more frugal consumers and ultimately falling prices.

But there is another problem. While the developed world is attempting to deal with headline inflation rates of 4% or more, China is looking at 7%, and rising. The Chinese growth engine has reached somewhat of a watershed. The productivity gains experienced in the twenty-first century have plateaued as wages have risen, while at the same time the renminbi is being quietly revalued. The artificial peg of the renminbi to the US dollar has been a significant reason why China has been able to export deflation. As both commodity prices and the renminbi rise, Chinese manufacturers are seeing their paper-thin margins vanish. The only solution is to raise prices.

The developing economies of the world are all now facing inflation problems. But at the same time, the developed world is suffering a credit crunch. The credit crunch began with falling house prices in the US. Falling house prices cause consumers to curb their spending, which is deflationary. House prices are now also falling in the UK and Europe. The credit crunch has also brought to an end, at least for the time being, out of control financial leverage. The US central bank not long ago stopped worrying about the money supply as an actual inflationary problem, given credit markets are far more influential in creating “money” through sophisticated derivative instruments and leverage. Now that the developed world has lost its appetite for risk, and particularly leverage, the resultant effect is deflationary.

And that brings us back to the US economy, which may or may not actually fall into recession but at the very least is slowing considerably. The sheer size of the US economy, and power of the US consumer, who represents 70% of that economy, means that a US slowdown must have a deflationary effect across the globe. It then becomes the sixty-four million dollar question as to whether the slowing US economy will affect slowing in China and other developing nations. It’s a toss up between the global power of the US economy and the sheer pace of Chinese growth which has now shifted its focus from the export to the domestic economy.

If the US slowdown does cause a flow-through slowdown across the entire globe, then inflation should only be a short term issue. If developing nations remain relatively unaffected, then inflation pressures will remain at least until monetary policy tightening has its desired effect. The Fed is still in cutting mode, but it has indicated that rates will be quickly shifted back up again at the first sign the US economy has stabilised. In the more recent era of central bank inflation control, double-digit inflation levels are no longer thought possible.

And then there’s those short term supply shocks. When the snow melts in China, the floods subside in Australia, and the power comes back on in South Africa, relevant commodity prices will once again fall. And when there’s peace in Iraq, peace in Nigeria, Iran and the US resolve the nuclear issue and Venezuela reaches an agreement with the US on nationalised oil production, there will be nothing left to hold up the oil price.

The only problem is, out of all of the above the only real possibility of a deflationary force in the short term is the Australian situation. Supply constraints in the coal industry have come about just as coal contracts are being renegotiated for the year with Japan and Korea. At the same time, China is looking at becoming a net importer of coal. One reason for this is the country simply needs more power. The snow will surely melt, but the lack of sufficient power in China will persist. And the power outages in South Africa have nothing to do with weather. South Africa simply needs more power. India also needs more power. Demand for commodities will persist.

In the case of oil, well Middle East peace is, of course, but a pipe dream. There is also a strongly held belief that OPEC does not actually have any room to increase production in any meaningful way. We’re not here to get into a discussion about peak oil, but oil supply is not a given irrespective of whether demand falls. And China has discovered the car.

Another factor to consider is the US dollar, for the greenback is the global currency by which commodity prices are measured. A falling dollar means higher prices, and the dollar has now fallen to new lows on an index basis. If the US economy does indeed recede and the Fed continues to cut rates, the US dollar should fall lower, pushing prices higher. That is, unless the rest of the world slows, causing monetary policy easing elsewhere. In that case, the US dollar will rise again, and commodity prices fall. But while inflation persists, other countries will not cut rates. There’s really a lot of Catch-22 going on here.

So, are we facing persistent global stagflation? Or will the current spike in commodity prices prove only a short term phenomenon? At present, the weight of argument favours the latter. In contradiction, the US bond market currently does not. Nor does the gold market. Volatility of financial markets is a clear and present indicator there is a great deal of uncertainty in the world at present. The game has yet to play out.