Feature Stories | Mar 23 2009

By Greg Peel

Simple modern economics – that which suggests financial systems are constantly attempting to find a level of equilibrium, and hence that prices will move towards the equilibrium point – dictates that the level of an exchange rate between any two currencies will be determined by the differential in interest rate between those two countries.

If your own country offers only a 4% return on its government bond but another country offers 7% then why wouldn’t you invest in the bond of the other country instead? The answer is that the exchange rate should already reflect that differential, such that your equivalent investment offshore will convert a lesser nominal value. In a perfect world the interest collected on the 7% bond on lesser value will equal the 4% collected on the greater local value and the net difference would be zero. If indeed you could enjoy a higher net return from overseas then not only would you decide to make your investment overseas, you would borrow as much money as you could locally to invest overseas at the higher rate and do it till the cows came home. This is called “interest arbitrage”.

Clearly interest arbitrage could not exist, except maybe momentarily, otherwise we’d all be doing it. And then the prices would need to adjust either in interest rate and/or in exchange rate until the arbitrage window closed, given the sheer demand for free money.

But it does.

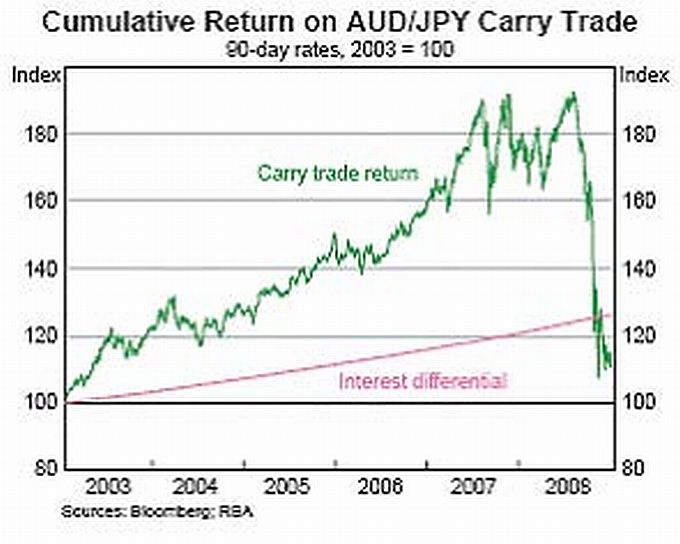

Or at least, it did. Under unusual circumstances, such interest arbitrage windows can remain open for a longish period of time. Such events belie modern economics which assumes all such windows must snap shut fairly quickly. But between the years of 2003 and 2007, one such window remained steadily open. It was the interest rate differential between the Japanese yen and many other higher-yielding currencies, such as the Australian dollar.

The Aussie is said to be a “commodity currency”, given our most important source of wealth is our natural resources. Thus when commodity prices are strong, the Aussie is strong. However, this equation only works indirectly. At the end of the day, the only factor determining the value of the Aussie is the Australian interest rate. But the interest rate adjusts to commodity prices.

After the mild recession Australian experienced in 2002 the Australian economy was put back on track by the emergence of China and its insatiable demand for commodities. In December 2001, the RBA lowered its cash rate to 4.25% which was, until recently, its nadir in recent decades. The Aussie dollar hit an all time low in 2002 of near US$0.47. In early 2008 the Aussie reached close to US$1.00 – a doubling of the currency value over the period in which China drove Australia’s own booming economy.

But as the Australian economy boomed, inflation became a risk. On that basis the RBA began raising its cash rate, eventually hitting 7.25%. Because markets tend to react faster than central banks, the Aussie always ran ahead of its interest rate as commodity prices pushed higher. So while it appeared it was commodity prices pushing up the Aussie, it was a trade conducted in the knowledge that the required interest rate adjustment would follow. By March 2008 the RBA lifted its rate to 7.25% while the US Fed, in response to the credit crisis, had cut its own rate to 2.5% by the end of the same month.

Thus we can say that interest arbitrage did not work except for short periods of speculation, because the interest rate differential between Australia and the US ultimately adjusted accordingly.

The story is different when one considers the Aussie against the Japanese yen. And it was early in this century that the concepts of modern economics, and self-correcting markets, began to break down.

In the period that the Aussie rate climbed from 4.25% to 7.25% the equivalent Japanese rate only made it from zero to 0.5%. This meant that the Aussie also climbed higher and higher and higher against the yen because the interest rate differential just kept blowing out and not correcting. The reason for this lack of self-correction lies in Japan’s infamous “decade of deflation”. The Japanese stock and property markets collapsed in 1990 and due to poor central bank and government economic management, Japan remained unable to drag itself out of the doldrums of deflation right through to the new century.

The interest rate differentials existing between Japan and high-yielding currency countries like Australia provided two separate parties with an opportunity. It gave birth to the “yen carry trade” (YCT).

The term “carry trade” refers to the traditional concept of “cash and carry”. If you buy wholesale widgets, for example, and sell them retail, then you would borrow money to pay “cash” for the widgets, and over the period you held the widgets before selling them you would pay both interest on the loan and storage costs which equate to the “cost of carry”.

Carry should be a cost, because you are paying out to hold the widgets. But if the cost is in your favour in a different transaction (such as exploiting a higher interest rate differential) then you have actually achieved “positive carry”. You buy something and hold it, and it pays you a positive return.

The first of the two parties to exploit the YCT were everyday Japanese citizens. The Japanese have a tradition of being diligent savers but this only worked against the Japanese economy because few were out spending money and consuming goods – that which is needed for positive economic growth. As we know all too well Australians were of a different mindset until recently, thus helping the Australian economy to boom. But while the Japanese saved their money for retirement, deflation ensured that their money could never grow. The prevailing interest rate was zero.

Because the Japanese interest rate had been zero for so long, its currency remained stable as well. Thus in 2003 Japanese citizens could look to the Australian cash rate of 4.25% and see a much better return. And so it was that, via specialised funds, Japanese citizens began investing in Australian bonds (amongst others including, in particular, Kiwi bonds). This should have been a risky trade, because in theory either the AUD/JPY exchange rate should ultimately adjust or the Aussie interest rate would adjust to “close the window”. But the YCT became much less risky because the Japanese economy was simply going nowhere.

Enter China. China’s demand for Australian commodities sent the Australian economy booming, resulting in the need for the RBA to raise its interest rate. Now the Japanese were looking at an even better return. As the Aussie rate continued to rise, more and more Japanese citizens invested their savings in Aussie bonds. When the differential really began to accelerate, the Aussie climbed ever more steeply against the yen. Pretty soon Japanese citizens took up an even riskier trade – that of margined forex trading. This became the realm of the Japanese housewife – stuck at home while her husband dutifully went off to work. The famous “Mrs Watanabi” (a fictional representative of such Japanese housewives) spent her days selling yen and buying Aussie – and cleaning up, so to speak. This was not an “investment” as such, it was simply a swap trade.

The second of the two parties to exploit the YCT were hedge fund traders. Hedge funds could borrow funds in yen at zero and invest them anywhere in the world for “positive carry”. Australian bonds were popular as a less risky trade (sovereign bonds are low risk) but hedge funds ploughed their free money into anything from emerging world stock markets to commodity funds, and into such instruments as high-yielding mortgage-backed securities (the now infamous CDOs).

Together, the two parties spent their days selling yen and buying Aussie (and other currencies including the US dollar). So popular was the YCT that it became self-fulfilling. Instead of exchange rate differentials returning to equilibrium (and thus closing down positive carry) as modern economics suggested it should, demand for the YCT simply pushed the differentials wider. It became a bubble, and bubbles will always eventually pop.

Research conducted by the Reserve Bank of Australia has found that while the two parties had a similar agenda, they actually reacted in different ways. The movement of the Aussie against the yen over the period has not simply been a straight line – there have been periods of ups and downs just as there is in any market. So the more conservative Japanese retail traders tended to use these undulations to their advantage, adding to YCT trades when the Aussie dipped and taking some money off the table when the Aussie ran strongly. In so doing, they actually ensured some stability in the market by reducing the level of volatility. If you’re playing a risk game such as positive carry, stability is a good thing.

The hedge fund traders (and other speculative players) responded differently however. They were looking more for the quick buck and had a lot of leveraged money at stake, so they were the momentum players. They would keep jumping in as the Aussie rose and then quickly jump out as soon as it fell, with substantial profits in tow if they reacted fast enough. The hedge funds had a short term horizon while the Japanese citizens were looking more long term – towards retirement.

The difference in strategy was to unfortunately prove very costly for the Japanese. As the global credit crisis began to play out, there were some sharp ups and downs in the YCT. Hedge funds were jumping out at the first sign of risk but the Japanese saw such drops as a chance to buy more for the long haul. When Lehman Bros fell late last year, the world changed. Suddenly it was apparent that no one was immune from the ravages of a global recession given the extent of credit built up across the globe (a lot of it in the YCT) and that included China, and as such Australia as well.

The world began to sell the Aussie dollar rapidly as commodity prices collapsed, in anticipation that the RBA would need to cut the interest rate, which it soon began doing dramatically. Hedge fund YCT traders madly dumped their positions but they were getting out first. When suddenly it looked as if the YCT was headed for disaster, the Japanese realised the game was up. Instead of buying the lower priced opportunity, they, too, decided to ditch. But they were slow to move.

The window slammed shut. The YCT had helped pushed the Aussie ever higher over a number of years and the rapid unwinding of the YCT helped push the Aussie from near parity with the US to around US$0.65 in a heartbeat.

The Mrs Watanabis of the world with their margined forex positions have been devastated. The more conventional Japanese investors in Aussie bonds have seen their previously growing nest eggs crunched.

TD Securities’ global economist Stephen Koukoulas notes the daily average turnover of Japanese margined foreign exchange trading had reached US$70bn by the September quarter 2008, representing 20% of all yen trading. Two years earlier that figure was only US$10bn.

The YCT has proven to be a major contributing factor to the great credit bubble collapse. Modern economics suggested such a disparity as the YCT could never last long, for prices must adjust when disparities occur and bring the market back to equilibrium. But the unusual situation of a deflated Japanese economy didn’t really correlate with such theories. Nor does modern economics pay sufficient heed to the nature of “irrational exuberance” – that which causes bubbles to form as more and more players (often with less and less knowledge) jump on a winning bandwagon. The longer a bubble is allowed to grow unimpaired the bigger it gets, and the bigger the eventual bust must be.

It must also be noted that major bubbles in the same market tend to form decades apart. The reason for this again runs contrary to modern economics, which assumes that all available information is passed on quickly into prices. If you have been in a bubble and bust before, you will be wary of making the same mistake again. But if you are part of a new generation that has never experienced a bubble and bust, you will not appreciate that another bubble is forming. Information will be treated differently and thus equilibrium will not be achieved.

The YCT is now likely dead. For starters, all major economies have been busy cutting interest rates so there are no differentials of note to exploit except those offering tremendous risk (Iceland, for example, has been putting its interest rate up instead of down to attract foreign investment, but Iceland is broke. Default becomes a major risk).

The question is will carry traders rush in once more as soon as less risky opportunities again present themselves (if, indeed, they do)? Or has the world, and Japanese housewives in particular, now become once bitten, twice shy? If the latter is the case, then a return to the heights of global markets in 2007 could be another generation away.