Feature Stories | Jul 30 2009

This story features BHP GROUP LIMITED, and other companies.

For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: BHP

The company is included in ASX20, ASX50, ASX100, ASX200, ASX300 and ALL-ORDS

(This story was originally published on July 22, 2009. It has now been re-published to make it available to non-paying members at FNArena and readers elsewhere).

By Greg Peel

It is now appreciated that since the end of last year, China has implemented a rapid increase in commodity imports to take advantage of GFC prices. While this may entail restocking of inventories, building strategic reserves in lieu of US bond investments, and local trader speculation, it is clear all roads also lead to one decisive factor – China’s massive infrastructure stimulus. It started with copper and iron ore, and spread into aluminium and other metals. All base metals have recently ridden the upswing, to the great surprise of analysts. They had expected a long period of price weakness as a result of global economic downturn.

One of the recent stars has been nickel. Nickel’s primary purpose in life is to turn regular steel into stainless steel. Clearly global steel production took a tumble in 2008, and outside of China is not really showing exciting signs of immediate recovery. Chinese steel factories were also put on hold, as were the country’s nickel smelters. But recently, things have started to change.

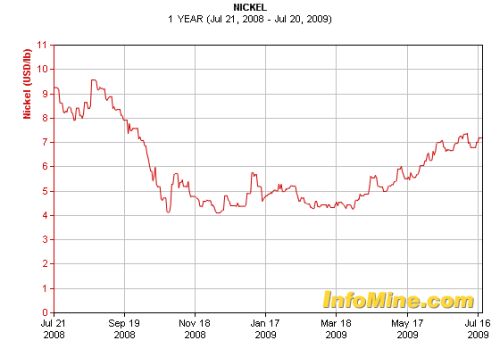

The following one-year chart shows the nickel price has now managed to bounce off its post-Lehman nadir just above US$4/lb and has rallied a substantial 75% to over US$7/lb.

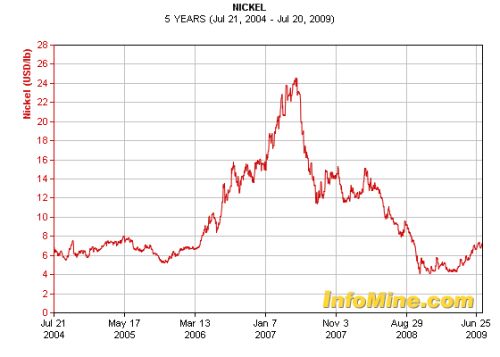

This is an impressive feat, at least until one stretches out to a five-year chart:

Looking at this chart, one can draw two conclusions. Firstly, a 75% price jump may be impressive but in the wider scheme of things, nickel is still only back at 2004 levels. But secondly, look at the upside potential! Were nickel to return to US$24/lb, that’s another 243% from here. If this were ever to happen, one must first appreciate how nickel ever got to US$24/lb in the first place.

Clearly the driving force was China, which entered the century on a steel production binge as it ramped up its global manufacturing export market and Western countries began to outsource their manufacturing processes to where labour was cheapest. But this also caused a huge widening of the trade imbalance between China and its biggest export market – the US – such that the US dollar weakened considerably over the period and pushed metals prices higher still. Then in came the speculators, although this time the driving force was commodity funds and mutual funds buying commodities directly for the first time via listed investment vehicles.

The fact that nickel traded as high as US$24/lb, whereas bellwether metal copper reached only just above US$4/lb at the same time, immediately tells us that nickel is not nearly as globally abundant. Its price boom was thus more spectacular than that of copper, but so also was its bust. Indeed, all base metal prices busted around the same time in early 2007, for the simple reason manufacturer margins reached their limits. Profits were no longer available.

There is also an important distinction between the various base metals. If you want to produce electrical wiring, for example, then copper is your only viable answer. If you want to build lightweight but robust machinery, then you have little choice but to use aluminium. If you want to put a battery in a car, well lead is still your only real option (except that the new breed of electric cars use lithium).

If you want to make something simple like a food container, then steel is your first choice. But you can also use tin, as was once the case. We don’t still call steel cans tin cans for nothing, but now they are merely tin-coated. In some applications, steel is substitutable. And substitutability is a very important factor in base metal pricing. Because if you want to galvanise steel, zinc is your first, but not your only choice. And if you want to make stainless steel then nickel is your go-to metal, but chromium and other substitutes can also be used, or lower nickel grade steels can be used as a substitute in production. In other words, if nickel is too expensive then alternatives will be found.

Thus in early 2007, the speculative bubble burst for nickel given demand suddenly waned at the price. The metal returned from US$24/lb to a more comfortable level between US$12 and US$15/lb until the GFC sent it spirally downward once more.

But that’s not all of the nickel substitution story. To understand more, one needs a bit of a lesson in metallurgy. Fortunately the UBS metal analyst team has recently provided such a lesson.

Nickel is found around the globe primarily in two distinct forms of deposit – nickel sulphides and nickel laterites. Sulphides can be found in open cut mines but more predominantly now are found in underground mines. Laterites tend mostly to be found in open cut mines. This means the actual cost of recovering the initial ore is cheaper for nickel laterites. But that’s where their economy ends.

Just as one rarely finds gold without copper, or vice versa, nickel has a love affair with cobalt. In order to produce nickel concentrate, one must first separate the nickel from its cobalt by-product. Nickel found in sulphide form contains a much higher grade – up to 20% nickel. Nickel laterites typically only contain 1-2% nickel, as well as a smorgasborg of other elements.

Nickel can be reduced to concentrate from sulphides by simple and long-proven floatation technology. It is then smelted to produce 75% nickel matte which is finally refined ready for use in stainless steel production. The process of extracting nickel concentrate from laterites is, on the other hand, technologically difficult and expensive. The process only has a recent history due to the sudden surge in the nickel price, and has not been perfected. BHP Billiton ((BHP)) may have closed its Ravensthorpe nickel project due to the fall in the nickel price, but the reality is Ravensthorpe is a laterite deposit and the project’s high costs were mostly due to unreliable technology.

This explains why nickel laterites represent around 72% of the world’s total nickel reserves, but nickel sulphides account for around 60% of current global production.

To extract nickel from laterites one can adopt a ferronickel smelting procedure, which doesn’t cost that much to set up but uses vast amounts of expensive energy to run, or autoclave leaching, which is expensive to set up but cheaper to run, or nickel pig iron smelting, which is an old form of technology but only results in a very low nickel grade product.

A recently popular form of autoclave extraction is High Pressure Acid Leaching (HPAL). As the process doesn’t use nearly as much energy as ferronickel smelting it should be cheaper to run, but sulphuric acid under high pressures and temperatures does tend to cause expensive wear and tear on equipment. And while ferronickel smelting is beholden to energy prices, HPAL is beholden to sulphuric acid prices, which also shot up astonishingly last year. It was this price rise which rendered Minara’s ((MRE)) Murrin Murrin nickel project uneconomical.

Nickel pig iron (NPI) smelting had largely been consigned to the history books until the Chinese began ramping up the process once more when the nickel price boomed. It basically means blending nickel laterite ore with iron ore to produce a lower grade feedstock for stainless steel production. Chinese NPI accounts for about 5% of global nickel supply and thus acts as the “swing factor” in global nickel demand, as UBS describes it, when higher grade supplies are tight. The cost of NPI production can be anything up to about twice that of other methods. There is an ofsetting factor, however, in that when the nickel price is high so too are the prices of the process’s by-products – iron, cobalt and chromium.

Hence the nickel substitution story is a slightly more complex one. The 2007 price bust was assisted by laterite processing becoming economical given the high price of nickel. Across the globe, mining majors and nickel juniors alike began to ramp up laterite projects, and the Chinese jumped into NPI production. Metal analysts assumed the world was about to become awash with nickel. Yet realistically technological problems were as yet unresolved, and the nickel price may well have recovered somewhat if it wasn’t for the GFC. A US$4/lb nickel price means laterite projects cannot run at a profit. On that basis, UBS expects the global supply of nickel to contract by 16% in 2009.

And one might wonder whether laterite nickel production might ever fully recover, given its costs and problems and despite its greater abundance. However, there is one more important factor to consider. The world is running out of viable nickel sulphide deposits.

UBS notes the number of new sulphide discoveries have dropped significantly over the years. There are three big projects in Brazil, Tanzania and Western Australia (owned offshore) yet to commence developement. Beyond that, a plethora of remaining potential start-up projects across the globe are all laterite. Given laterite technology has yet to be refined to a reliable level, the analysts suggest future nickel production and price forecasting is going to be difficult.

Not that it isn’t already an inexact science, it would seem. Independently, Barclays Capital suggests global nickel supply has already fallen 22% year to date given the sheer number of mines which have either temporarily or permanently shut down. At the height of the nickel price, 100% of all the world’s nickel mines were operating at a profit, Barclays suggests. That figure is now 50%. It’s not just about the nickel price, it’s about credit issues as well. At the same time, Chinese “apparent” consumption has grown 33% year to date.

But it’s all China so far. There has yet been little sign of recovery in the global stainless steel market outside China, and despite Chinese imports, London Metals Exchange inventories failed to mark any substantial declines in the June quarter. There are LME warehouses all over the globe, including in China, suggesting whatever nickel China bought in the first half has merely been stored.

Is this simply aforementioned restocking? Or does China have a use in mind? Barclays believes the latter, suggesting the disconnect between price performance and apparent fundamentals in the first half ’09 will give way to a fundamentally “more robust” market in the second half. Indeed, the analysts believe “the overall tone is one of optimism”, even if you take into consideration a number of mines that will probably restart, Chinese NPI production which could ramp up again and the possibility that Chinese metals speculators will indeed release stockpiled nickel into a more positive demand-side.

In the immediate term, there is already a specific supply constraint to deal with. Vale’s Sudbury and Voisey’s Bay nickel operations in Canada, which together represent 8.3% of projected 2009 global supply, have shut down for maintenance. That’s not so much of a problem, except that the workers have decided to strike over pay conditions rather than return after maintenance is complete next month. Don’t underestimate labour strikes in the base metals industry. They can go on forever and cause serious supply shocks and price jumps.

In the more medium term, Barclays believes the restarting of idle mines will keep the market at a more neutral stance. The latest industry data suggest that at US$7.25/lb for nickel, all of the world’s nickel mines still in operation are doing so profitably given the subsequent fall in the cost of energy and inputs such as sulphuric acid. Mines such as BHP’s Ravensthorpe will eventually ramp back up, the analysts suggest, if current nickel prices prove sustainable. In the second quarter, 40kt of Chinese NPI production came back on line. Beyond 2010, planned new mines make the supply view over the next three years “solid if not spectacular”.

But some mines will never restart, Barclays notes. Other more marginal mines will hold off until it is abundantly clear nickel demand has returned before going through the costly process of firing up again. In summary, the analysts suggest:

“The supply-side signals then from nickel are mixed – higher prices will clearly support new mine projects, but obviously there will be a delay in reaction and moreover there are not a great number of potential high grade sites available even if the profit incentive exists.”

Back to the supply-side. While China’s “apparent” nickel consumption may have increased 33% ytd, Barclays notes it is China’s specific net imports of already refined material that have been spectacular. That figure is up 44% from January to May and May monthly imports alone represented a 139% increase on the levels of May ’08. Year to date volumes represent 17% of total world demand compared to 10% this time last year, with May hitting 26% compared to 9% in May ’08. In the meantime, global nickel consumption (ex China) is down 32%.

Barclays is in little doubt that Chinese nickel demand is not totally misleading. “First and foremost,” say the analysts, “relative to the rest of the world, China’s recovery from the global financial crisis and its repercussions has been far more rapid and sustained”. Fiscal stimulus and expansion of private credit have progressively indicated “an expansionary state of economic activity”. Inventory restocking and private speculation have clearly occurred, but the analysts note Chinese stainless steel mills are ramping up production and the majors, such as Baosteel, have “expanded production significantly”. Also noteworthy is that higher nickel-content grades of stainless steel have gained an increasing share of production.

Domestic supplies of refined nickel are only running at about a quarter of demand, Barclays notes. And the high price of nickel in 2007 means supply of both scrap nickel and scrap stainless steel are in shortage. Nevertheless, the risk is that ramped up NPI production and quiet releases of speculative stockpiled metal, plus the likelihood legitimately stockpiled metal might be run down until demand trends are confirmed, will all conspire to make the second half of 2009 difficult to gauge.

The UBS analysts have already noted price forecasting will be difficult, and despite maintaining an optimistic “tone”, the Barclays analysts would obviously not disagree. Yet Barclays is happy to err to the positive side, suggesting:

“Beyond deviations in demand over the next six months, it is quite clear that China will remain a firmly supportive demand dynamic for nickel in coming years.”

It is, however, a different story elsewhere. Barclays suggests the OECD countries are stuck in limbo, between a destocking and restocking phase, not game to take risks until a clear improvement in global nickel demand emerges. The recent jump in price has meant some increase in production, but this can be misleading. The analysts do assert, however, that the restocking phase will gather pace as soon as clear signs of improvement in end demand feed through. They believe this will happen in the December quarter after the traditional northern summer slowdown.

Such a view correlates with a widely held belief the world will see tentative economic recovery by year end.

To conclude, Barclays believes that despite a tightly balanced market over the next 18 months, nickel market fundamentals offer “an increasingly supportive outlook”. The analysts are forecasting an average nickel price in the second half ’09 of US$6.80/lb, rising to an average US$7.70/lb for 2010.

UBS recently upgraded its forecast to US$7.00/lb in 2010 and US$7.50/lb in 2011. The spot price at the time of writing is US$7.13/lb, although it must be noted that stock analysts prefer to pitch “average” price forecasts well under spot levels in order to provide a buffer against volatility.

On the local pure-play producer front, UBS prefers Mirabela ((MBN)) for nickel exposure.

Click to view our Glossary of Financial Terms

CHARTS

For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: BHP - BHP GROUP LIMITED

For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: MRE - METRICS REAL ESTATE MULTI-STRATEGY FUND